Editor's note: this is the second installment in a series on Game Theory. If you are unfamiliar with The Prisoner's Dilemma, it is recommended that you read the intro to the series before diving into this post.

From an economic standpoint, militaries are a huge waste of money. Countries around the world spend significant portions of their budgets in order to outfit and equip an army with personnel, vehicles, and weapons...and their sole purpose is to destroy other armies' personnel, vehicles, and weapons.

Now, you can make the argument that armies can serve other purposes than destruction, such as aiding with disaster relief, but many countries also have nuclear weapons, which are pretty much a one-trick pony. A nuclear arsenal takes an insane amount of money to develop and maintain, and all nuclear weapons can really do is level cities.

If the main goal of humanity is to build a better world so that everyone can live a happier, more comfortable life, then why on earth do we spend so much money on things made to destroy all that we have built?

A rational (and naive) person might say "can't we just all agree to get along so that we can stop wasting money on military advancement and shift the resources towards more humanitarian efforts?"

And that's a hell of an idea, but if you read my past article on the prisoner's dilemma, then you can probably see where this is going.

But I mean, seeing the Thunderbirds in person was pretty awesome, so maybe not a complete waste of money

Countries Are Basically Prisoners

In the prisoner's dilemma, we learned that if two people who have no loyalty to each other are given the choice between cooperating with one another (with the chance of a medium payoff, but at the risk of a very low payoff) and defecting against one another (with the possibility of a larger payoff and the risk of a slightly low payoff), then the most logical decision to make is to defect.

Now consider that each country in the world is a prisoner in this illustration. The first criteria of the prisoner's dilemma is that the prisoners have no loyalty to each other. This isn't exactly the case on the world stage, as countries definitely have alliances and trade agreements with other countries, which gives them some degree of loyalty, but I'd argue that a country's loyalty towards a fellow country is only as strong as its benefits from that country.

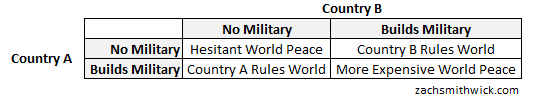

For this illustration, let's assume that the countries in our hypothetical world are quasi-loyal to each other. They get along, trade a fair amount, but if an opportunity arose to take over another country, they'd probably do it. With that in mind, it's fairly easy to see how the prisoner's dilemma scenarios play out:

As with the traditional prisoner's dilemma, the bottom right square is the "Nash Equilibrium", i.e. it's the stable state that the system will eventually take if all players are playing logically. Now, there are a few ways that this game can differ from the traditional prisoner's dilemma, which I'll outline later, but for now let's break down each state.

Mutual Disarmament

This is the top left state, and it has two basic properties: it's the most ideal for all parties and the least stable. It's the most ideal because it features the countries existing independently and trading with one another without spending lots of money to outfit respective militaries. It's the least stable because each country stands to gain a fair amount by building a military, and they also stand to lose a fair amount by not building one.

Think about it, would you be very comfortable in a world where all the countries made a mutual pact to not have militaries? It might start off okay, but eventually we'd start looking at footage from another country and go "hmm, Artland citizens sure seem to be getting in shape...and they sure do make a lot of really big cars that can handle extreme terrain...and they are all really good at hunting with long rifles...and their airplanes sure do have a lot of armor just to carry passengers..."

Eventually, everyone's anxiety would hit a boiling point and the country would scramble to build and equip a military, whether or not the other country was actually outfitting one of their own. Better safe than sorry, right?

Singular Disarmament

Let's assume everyone in your country got worried that other countries were stocking up on arms so they decided "well, let's stock up on arms just to be safe."

As it turns out, the other countries really weren't stocking up on arms, and now your country has an extreme tactical advantage over the rest of the world. At this point you have a choice, you can either start invading people or just sit back and rest easy that you're the master of your domain. A fair amount of people in your country start saying "hey, we've got a massive army that we paid a lot of money for, might as well get our money's worth", and other people say "it's not right to take land from other countries, we should just stay put and be glad for our safety."

The leader of your country is very indecisive, so he bounces these ideas around in his head for awhile, which leads to...

Mutual Armament

The massive push your country made for a huge military did not go unnoticed by the rest of the world. Now, other countries are scrambling to get their militaries put together, because you don't want to be the country who is left without a military when everybody else has one. Because your leader was indecisive, he missed the moment to attack other countries and take advantage of his large unrivaled military, and now attacking other countries would come at a much greater risk. The decision to stay put is effectively made for him, and so the world resumes its hesitant peace, except now they are sitting on a vast arsenal of hi-tech weapons.

That's probably about how that scenario would play out, but there is a slight wrinkle to the narrative: what if the cost of outfitting a military was more than the cost of getting invaded?

Strategic Armament

Until this point in the prisoner's dilemma analogies we've assumed that the cost of cooperating if the other player defects (the top right state in the chart if we are player A) is greater than the cost of mutual defection. This might not always be the case, though. In our military example, it's quite possible that the cost of building a military that is competitive with the other countries' would bankrupt your own country and cause economic collapse. On the other hand, if you didn't build a military and got invaded by another country, then things might not be too bad. Maybe the other country has good policies and their citizens are pretty happy, and while you would prefer to stay independent because of pride and such, life wouldn't be terrible should you get invaded.

If this is the case, then the game gets more complicated. The question of whether or not to defect and build a military becomes dependent on the probability that the other countries defect and that one of them chooses to invade you. If it's a low risk of invasion by other countries, then the most rational decision is then to not build a military, because doing so would only be a fruitless cost.

If there is a higher probability that the other country will attack you, then the strategy could then be to build a small military that would not be competitive with the other countries', but would be big enough to at least make them think twice about attacking.

Of course, there is a final option to make friends with a neighboring country that has a military and mooch off of their protection (I'm looking at you, Canada).

This incredibly serene lake brought to you by the United States Armed Forces, protecting Canada's ass since 1867

So watch it, Canada, if you start talkin' shit then we're gonna take all your maple syrup...